We have already seen in the basic-communication tutorial how services can publish and consume messages.

If you haven’t read it yet, I highly recommend going through that tutorial first.

In real-world applications, we typically work with two primary types of messages: Commands and Events.

In this tutorial, we will explore these concepts through an example.

Message Types

Commands

A command instructs a service to perform a specific action.

It is typically consumed by a Single Consumer Application. If Multiple Consumer applications subscribe to the same command message,

they will compete to consume it(Competing Consumer Pattern).

Events

An event indicates that something has happened.

An Event is typically consumed by All Consumer Applications that subscribe to that particular event message(Publish-Subscribe Channel).

Naming Conventions

When naming messages, the message type determines the tense and structure.

Commands

Commands use a verb–noun sequence, following a tell-style format.

Examples:

UpdateCustomerAddressUpgradeCustomerAccountSubmitOrder

Events

Events use a noun–verb (past tense) sequence, indicating something has already occurred.

Examples:

CustomerAddressUpdatedCustomerAccountUpgradedOrderSubmitted,OrderAccepted,OrderRejected,OrderShipped

These are just conventions. To OpenTransit, commands and events are simply regular messages.

Implementation

Here is a basic implementation of the pattern.

The messages and Consumers classes are kept on the Shared Project.

Command Implementation

Since the Receive Endpoint natively implements the Competing Consumers Pattern, no additional configuration is needed.

In the Example Project you will see both ApplicationA and ApplicationB subscribed for the ProcessOrder message.

Here, ApplicationA and ApplicationB compete for each ProcessOrder message.

Note

In this example, Both ApplicaitonA and ApplicationB consumes the same ProcessOrder message. However, in real scenarios, a command is typically consumed by a single application.

We structured the example with multiple consumers for Command to help illustrate how the Receive Endpoint and consumer behavior work in practice.

Events Implementation

To implement events, we need to create multiple ReceiveEndpoints, one for each consumer application.

This is because when an event is published to its PublishEndpoint, it is routed to every ReceiveEndpoint associated with that message. Since each ReceiveEndpoint here belongs to exactly one consumer application, there is no competition between them. As a result, all subscribed applications receive the event.

In the Example Project, you will see that both ApplicationA and ApplicationB subscribe to the OrderProcessed event, but each uses a different ReceiveEndpoint configuration.

x.AddConsumer<OrderProcessedConsumer>()

.Endpoint(e =>

{

e.Name = $"OrderProcessedConsumer-ApplicationA";

});

x.AddConsumer<OrderProcessedConsumer>()

.Endpoint(e =>

{

e.Name = $"OrderProcessedConsumer-ApplicationB";

});

Here, two Receive Endpoints are created for the OrderProcessed message: OrderProcessedConsumer-ApplicationA and OrderProcessedConsumer-ApplicationB, created by ApplicationA and ApplicationB respectively.

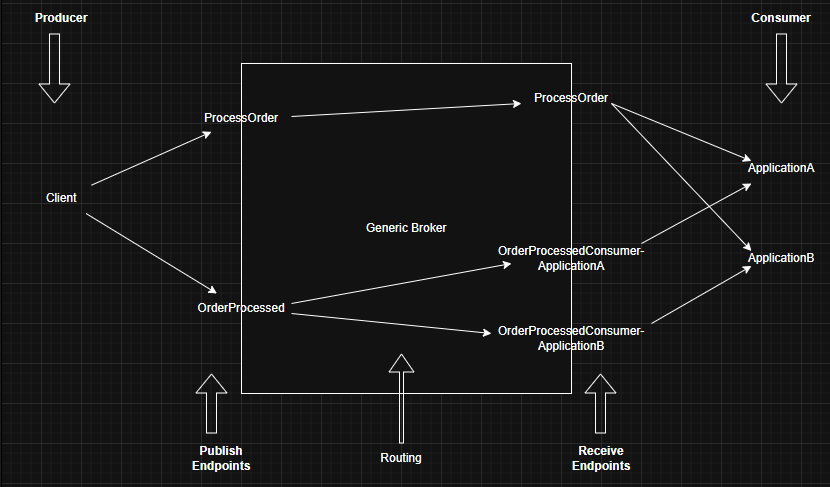

When the OrderProcessed message is published to its Publish Endpoint, the broker routes a copy of that message to each of the two Receive Endpoints. The diagram below illustrates this behavior.

Generic Broker Topology

So let's see how the topology looks like from a Generic Broker's Perspective.

Behaviour on having Multiple Instances of a Consumer application

In the example, we run only one instance of each Consumer. However, in a production environment, there may be multiple instances of each Consumer running in parallel. Will the system still behave as expected?

Let’s walk through it.

Assume there are 3 instances of each application: A1, A2, A3 and B1, B2, B3.

Commands

For Commands (e.g., the ProcessOrder message), all instances of both application(A1,A2,A3,B1,B2,B3) subscribe to the same Receive Endpoint.

They form a competing consumer group, meaning only one instance will consume each command.

This ensures the Command pattern behaves exactly as intended.

Events

For Events (e.g., OrderProcessed) the instances are basically divided into two Competing Group based on the application they represent:

- A1, A2, and A3 subscribe to a single Receive Endpoint (

OrderProcessedConsumer-ApplicationA). Only one instance among them will consume each event. - B1, B2, and B3 subscribe to a single Receive Endpoint (

OrderProcessedConsumer-ApplicationB). Again, only one instance in that group will consume each event.

Because each application has its own Receive Endpoint for the event, both Application A and Application B will receive the event, even though only one instance inside each application handles it.

This ensures the Event pattern also behaves as expected.

Conclusion

The behavior of Commands and Events remains the same even when multiple instances of a Consumer application are running.

Commands are consumed by exactly one instance, and Events are delivered to each subscribed application group.

Learning Points

In this document, you not only learned the differences between Command and Event messages, but also gained a deeper understanding of how Receive Endpoints and Consumers behave.

You explored how multiple Consumers compete when subscribed to the same Receive Endpoint, and how you can create multiple Endpoints for the same Message to isolate competing groups.

With this knowledge, you can design and configure any message topology that fits your application’s requirements.